This past month of April is World Autism Month, the international month dedicated to the awareness and appreciation of Autism and autistic people. Incidentally, both the second speaker for this year, Elizabeth Bonker, and I are on the Autistic Spectrum, although in different “shades”; because of this occasion, I would like to explain more about Autism, along with giving a glimpse of how a person experiences it in their lives.

A roughly three-year-old child plays a little bit wildly in the living room, even if his parents had warned him many times not to. He breaks a lamplight. His parents become angry at him and scold him; in reaction, the child bursts into laugh, driving the parents even angrier and causing the child to laugh even more.

This situation might seem paradoxical, yet it is an actual episode from my childhood: I was a child, and I did laugh when my parents scolded me. Despite the apparent strangeness of this event, it can be explained by the fact that I have Asperger’s Syndrome.

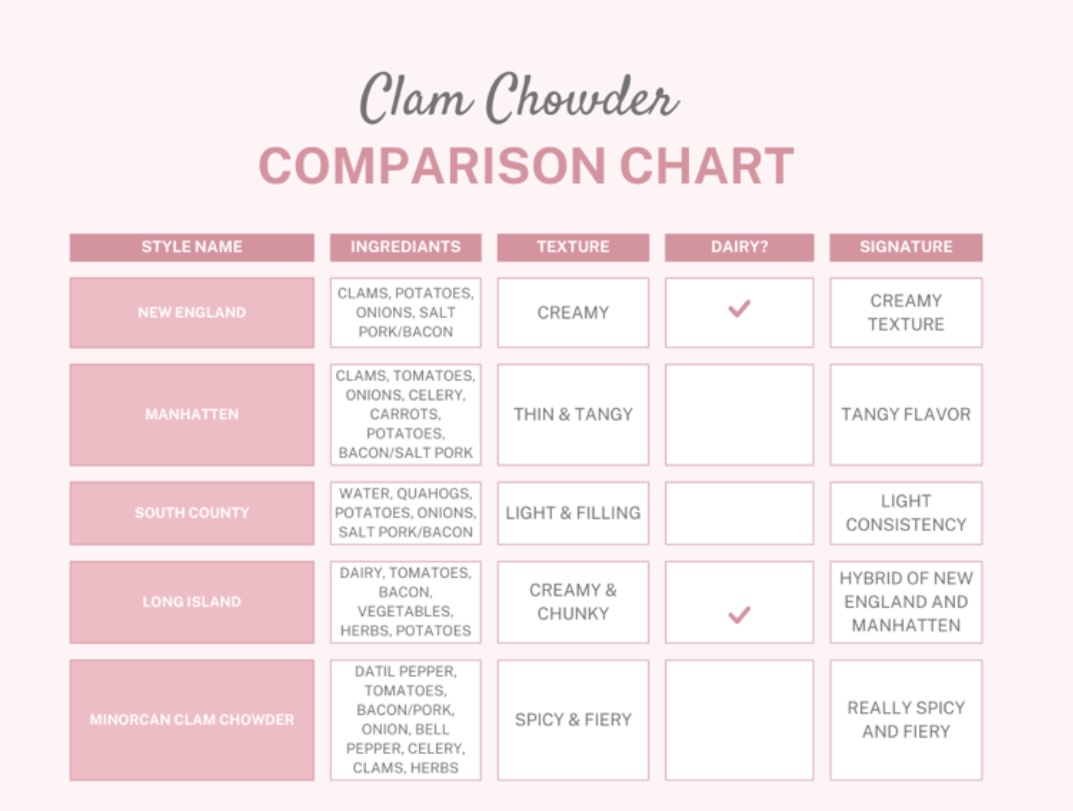

Asperger’s Syndrome is part of Autism Spectrum Disorder, often shortened to ASD; according to the National Institute of Mental Health, ASD is: “is a neurological and developmental disorder that affects how people interact with others, communicate, learn, and behave.” It is called a spectrum

because it is not one single condition; instead, autism is a combination of conditions that cause similar symptoms yet also differ from one another and are manifested in diverse degrees by each individual. In the same way, as visible light is composed of many different shades and colors (such as green, blue, red, and yellow) that are all forms of light, autism is composed of differing conditions having specific peculiarities but sharing a common structure, which involves changes in how a person communicates, learns, behaves, and forms relationships.

Asperger’s syndrome (the particular shade of autism I fall on) is characterized by difficulties in understanding other people’s emotions from their faces and gestures, problems in forming friendships, and, in some cases, an obsession with a particular interest. Nonetheless, this is not the

only way of viewing Asperger’s. In recent years, many people have come to view it as a form of neurodiversity, or a different way in which a mind can be structured, much like the different ways in which the same poem can be written using different rhyme schemes.

I can definitely relate to the symptoms described above: when I was a child, I found it hard to categorize the emotional expressions of other people, and this is the reason why I laughed when my parents scolded me (I did not understand that they were angry, and evidently I thought their faces were funny). I was also not prone to forming friendships, even though I did improve on this point; furthermore, I never had a particular obsessive interest.

The experience that each person with Asperger’s syndrome has with the syndrome itself varies from person to person. Thus, I cannot speak for every single “Aspie” (a nice term for referring to people with Asperger’s syndrome which I personally like). Nonetheless, I can provide a brief description of how I perceived being an Aspie, as well as some personal theories about what affects each Aspie’s view of Asperger’s.

When I was very young, I was simply not aware of being Aspie. Then, as I grew up (around 12 or 13 years old) I started to comprehend it, yet I came to view it as a curse that I wished to be rid of. It was only later, a couple of years ago, that I began to truly view it as a different way of being, neither inferior nor superior to other individuals‘ ways: I integrated Asperger’s syndrome into my identity.

In my opinion, something that impacts Aspies’ perception of Asperger’s is the availability of supporting techniques. Asperger’s syndrome is not an illness, and therefore there is no cure; however, there are a number of techniques that can be used to help Aspies overcome the most negative aspects and utilize the most positive aspects, a process akin to taking the spines off a rose. When Aspies have access and use these techniques, they prosper, come to understand and appreciate the ”gifts” that Asperger’s gives to them, and do not view the problems as menacing; by contrast, when they do not have access to these techniques, the problems overwhelm them and they see only the negative aspects: autism then appears as a foreign part of their character.

I would like to give you an example of such techniques: to teach me how to “read” faces (a process that other people learn automatically at a very young age) my therapist used a couple of puppets called “Peter and Mary.” These marionettes have detachable faces, with each possessing a set of faces expressing emotions in a very evident way (such as a sad face, a happy face, and so on). In addition, the faces were color-coded to show whether or not a state of expressed emotion was acceptable- being “green angry“ was fine, but “red angry” meant that the doll was freaking out and the puppets were used to re-enact situations which I confronted in daily lives, such as interaction with other classmates at school.

When Elizabeth Bonker did her conference, her words resonated with me and many other students following guest speakers. While she does not have Asperger’s syndrome, she is on Autism’s spectrum. Her words remind us of the necessity for each Autistic child, no matter what their nationality or socioeconomic position is, to receive a diagnosis and the techniques to both overcome their difficulties (whether not being able to read faces or speak) and use their gifts at best. It is through this accessibility that autistic people come to form their identities and find fulfillment because ASD does not have to mean “sad.”