The sky is bright blue with the sun shining warm in the middle. This may seem an irrelevant detail, if it weren’t that the part of the world where I was is known for its highly variable climate, jumping wildly from rainstorms to sunlight. This blue sky was hugging a curious ensemble of buildings, a menagerie of styles and periods. Rectangular buildings with marble-white columns that looked like ancient Greek temples shared yards with Gothic castles filled with towers, spires, and gargoyles, and with red-brick constructions straight from the eighties. In this college, history is like an onion, and the buildings are the layers representing each age and covering one another. Our destination was an ancient building made of stone, which students and staff called “The Long Room” and hosted the Library, which made that college famous. Indeed, as our guide told us, when one asked us where “the Harry Potter library” we had to point to that building.

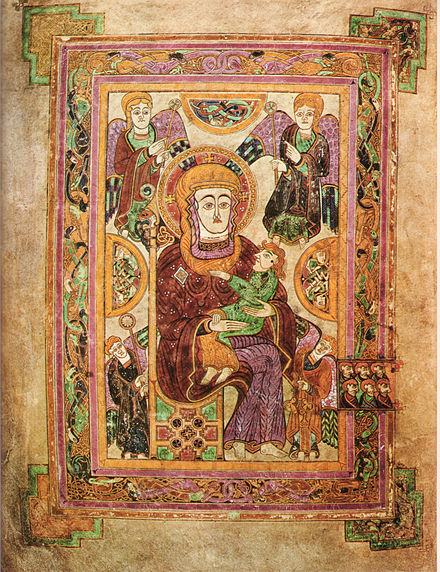

More specifically, we were there to see the Book of Kells, a 800 AD illuminated manuscript from Ireland containing the four Gospels in Latin, known for having the most intricate calligraphy and illuminations (drawings of animals, people, and objects decorating books in the Middle Ages) in the entire Western world and for being a testament of the interaction between Christian and native Irish traditions. It is currently held at Trinity College, Dublin, where I was accepted a few months ago and where I will likely spend the next four years. Since my family and I wanted to visit the College itself, we also decided to attend an exhibition on the Book of Kells.

The very first room was relatively simple. It was a vast room, filled with cardboards and screens with pictures of illuminations (drawings) from the Book of Kells itself. These were eerie yet stunning drawings of animals, objects, abstract symbols, and people that coiled themselves around the letters making up the Latin texts. Many of the animals had fantastical and symbolic traits, such as lions breathing a colorful air, relating to a medieval belief that lions could resurrect cubs with their breath, a belief which was also a symbol for Jesus Christ’s resurrection. All sorts of beasts, real and mythical, lions, tigers, dragons, snakes, peacocks, and eagles chased one another, danced, and coiled around the black letters and texts. Moreover, Celtic symbols such as spirals shared pages with Christian crosses, presenting that intertwining of cultures and religions which is constant in the history of the human species. The exhibition also described what materials were used to practically create the book. The colors for the illustrations were derived from minerals and natural pigments, such as blue from Lapis Lazuli, while a medieval type of pencil was wielded to write. The names of the scribes and artists are unknown, but analysis suggests that there were many of them, and they were likely the same people.

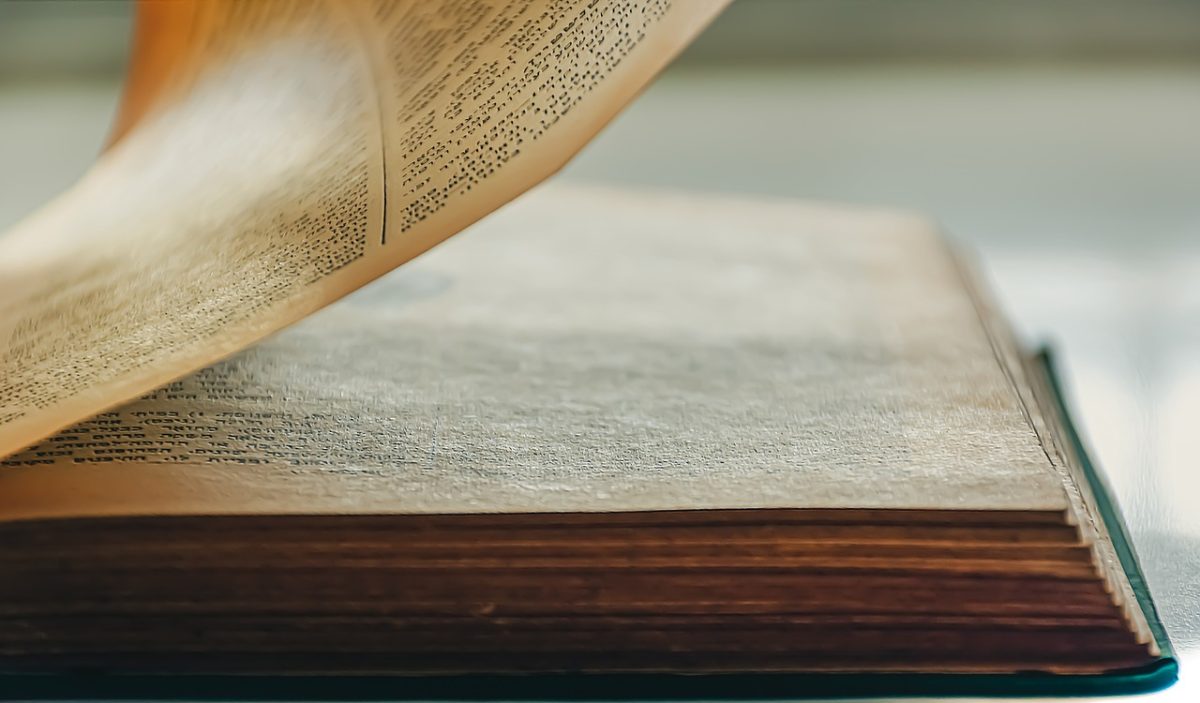

The next room showcased the book itself. When I saw it, I was shocked to realize how small the illuminations really were, and I felt overwhelming admiration for those artists and scribes who had spent so many years working at the best of their skills. I couldn’t help but imagine them, seated in dark and cold rooms at the abbeys, coldness biting at them; wet odors of mold filling their nostrils; the sounds of wind, animals, or the roaring sea coming at them from outside the windows; their eyes fixed on the blank page, filled with tiny black letters and those dancing, colorful figures around them which nothing but a candle brought to life.

The texts on cardboards and screens, along with a short film shown in another room, also described the history behind the Book of Kells. The manuscript was created in Iona, Scotland, by monks from the order of St Columba. These monks adapted the four Gospels while also adding complex illuminations, reinforcing the symbolism of the sacred narratives, pioneering a rare style later known as the Insular Style. Yet, the community was unsafe, as Vikings frequently attacked and pillaged it. Eventually, the monks fled by ship and underwent a dangerous sea voyage to Ireland. There, they traveled deep in the heartland and eventually found solace in the village of Kells, in whose chapel the book was conserved, becoming a cornerstone of the place’s spiritual life. Yet, in 1006, the book was stolen and was found two months later buried underground. While its golden casing would never be found again, the book itself was surprisingly unscathed. During the English Civil War, it was sent to Dublin for better safekeeping, and the book was stored in the budding (at that time) Trinity College, where it stayed for hundreds of years until the present day.

Between the book and the short film, we also visited the Old Library. This is the most iconic feature of Trinity College, Dublin, which inspired essentially every great and important library in works of fiction, such as the Jedi’s Library in Star Wars, Trantor’s Library in Isaac Asimov’s Foundation, and Hogwarts’ library in the Harry Potter series. Yet, the actual place was even more stunning than all these fictional magnifications. More than a room, it looked like a giant corridor, massive in width and height and stretching beyond eyesight in length. Each side was divided into two floors, and each floor was filled with shelves upon shelves. The two floors were connected through coiling wooden staircases, and the shelves were protected by cords to prevent people from damaging the oldest books. Indeed, many of the shelves were empty precisely because the books needed to be taken out and restored, as well as digitalized. Indeed, some short films in the room displayed this process. As strange as it might sound, the act of taking off the dust was the most impressive thing. Over hundreds of years, the dust had accumulated on the pages and covers to form bundles the size of small pebbles In fact, it was not so much that the books had to be cleaned as they had to be dug out of the thick white dust, like archeological findings have to be dug out of the Earth. It was like every minute had become a speck of dust, and the years and centuries had become stones. The walls were also lined with statues of authors who had contributed to the Library, from the Middle Ages to the present. Yet another short film explained the history of the Library, which had been established in 1592 with the founding of Trinity College itself and had grown over 400 years, amassing a collection of more than 6 million manuscripts and massive numbers of journals, maps, and even written songs. The Library even has a special legal status, thanks to which every book published in Ireland and the United Kingdom must have a copy of it placed there. In fact, the entire cultural history of these countries can be traced through the collection.

When visiting both the Book of Kells and the Old Library, I experienced both time and timelessness. They were here long before me or any other of my generation, and will still be there long after I have gone. The Book had survived for more than a thousand years, and had been seen and worked on by so many people that it can’t be counted. The Library has conserved thousands of authors and artists over the centuries, and will continue to do so in the future. The singular writers may have died, but that place still exists. It is through objects such as the Book of Kells and places like Trinity College’s Old Library that the human being is reminded that the universe did not start when they were born or opened their account on Tik Tok, but that it has an infinitely long history made up of countless past and future lives that interlace one another like illuminations and letters on the Book of Kells.

In other words, it is through these objects and places that we experience eternity.