Winter is coming to an end, and the signs of spring are popping up in every corner. While most trees stay resting in their dormant state, the cherry blossom trees are pioneers of their kind, one of the first to show their beautiful flowers. But the cherry blossoms at the Tidal Basin in Washington D.C. are more than just a pretty sight. They stand for the blossoming friendship between the U.S. and Japan and the power of one woman’s determination to achieve her dream.

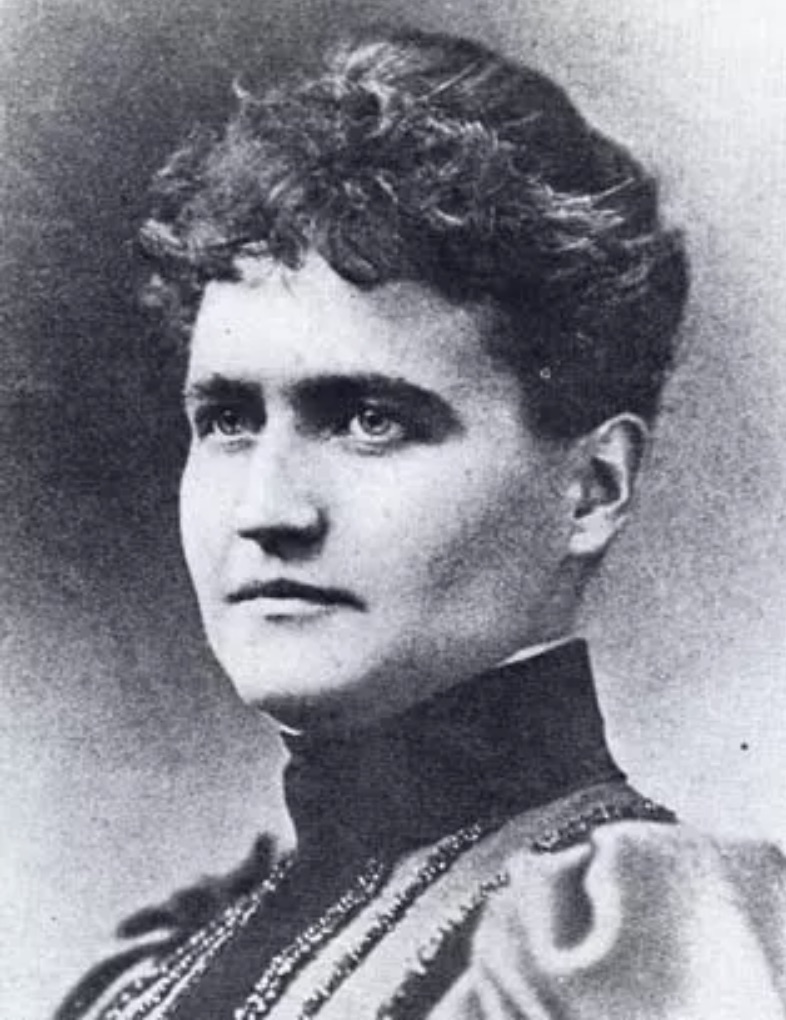

The history of these famed trees and their ties to the nation’s capital starts in the 1800s. The bridge between the two begins with Eliza Ruhamah Scidmore. Scidmore was born in 1856 in Iowa and became a well known world traveler, diplomat, writer, and travel photographer. She broke stereotypes and was a remarkable woman of her time. Perhaps Scidmore’s most famous legacy is her decades-long endeavor to bring cherry blossom trees to Washington D.C. She began visiting Japan in 1885 and fell in love with the sacred Japanese trees.

After her trip to Japan, she approached the Superintendent of the Office of Public Buildings and Grounds in D.C. about planting cherry blossom trees on the bank of the Potomac River. Her idea was denied, but Scidmore persevered and continued over an astounding 24 years to advocate for her idea.

“[…] since they had to plant something in that great stretch of raw, reclaimed ground by the river bank, since they had to hide those old dump heaps with something, they might as well plant the most beautiful thing in the world—the Japanese cherry tree.” wrote Scidmore.

In 1906, the U.S. Department of Agriculture Official Dr. David Fairchild had been “experimenting with and advocating for the introduction of Japanese flowering cherry trees in the United States,” according to the National Park Service. He decided to plant some cherry blossom trees from Japan in his backyard to see if they could grow in a mid-Atlantic environment.

Scidmore reached out to Dr. Fairchild in 1908 on the matter of cherry blossom trees. She discovered his experiment to introduce the trees to his yard was successful. Following these events, Scidmore wrote a letter to the First Lady, Helen Taft, which outlined her plan to raise money to plant the cherry blossom trees around the Tidal Basin. The first lady agreed and promised that the trees would be planted. Dr. Jokichi Takamine, a renowned Japanese chemist, asked whether First Lady Taft would accept a gift of 2,000 cherry blossom trees given in the name of the City of Tokyo.

In 1910, over 2,000 cherry blossom trees arrived in Washington D.C. However, to everyone’s dismay, the trees were infected and carried disease. Sadly, to protect the American farmers, the diseased cherry blossom trees were burned. In 1912, the Mayor of Tokyo, Yukio Ozaki, generously gave another gift of cherry blossom trees, this time increasing the number of trees to 3,020. First Lady Taft and Viscountess Chinda, the wife of the Japanese Ambassador, planted the first two cherry blossom trees near the Jefferson Memorial in Washington D.C. As a sign of gratitude in 1915, President Taft sent a gift of flowering dogwood trees, the state tree of Virginia, to the people of Japan.

Japanese Pagoda, gifted to D.C. in 1958 by the Mayor of Yokohama in Japan (Credit: NPS)

Fast forward to 1950, when Japan asked the U.S. for help to restore a grove of cherry blossom trees that had fallen into decline during WWII. The U.S. shipped budwoods of the descendants of the cherry blossom trees that were originally gifted in 1912 by Japan. This act came to symbolize the cycle of friendship and giving between the U.S. and Japan. Then, in 1954, the Japanese Ambassador of Japan to the United States, Sadao Iguchi, gifted the U.S. a 300-year-old stone lantern. The lantern is part of a set, with the other standing in Ueno Park in Tokyo, Japan. The gifting of this lantern celebrates the 100th anniversary of the first Treaty of Peace, Amity and Commerce between the United States and Japan.

This spring, the famous cherry blossom trees reached the sixth stage of their development around March 28th. People from around the country and DMV area flocked to marvel at the display of color. The National Cherry Blossom Festival started on March 20th and ended on April 13th, with celebrations including a kite festival and parade.

However, global temperatures continue to rise due to climate change, causing the blossoms to bloom earlier in the year. If this trend continues, the trees could start to reach peak bloom the first week of March. An additional negative effect on the trees is the changing sea levels. In the spring of 2024, the National Park Service announced a project to rebuild the seawall around the Tidal Basin.

“This critical investment will ensure the park is able to protect some of the nation’s most iconic memorials and the Japanese flowering cherry trees from the immediate threats of failing infrastructure and rising sea levels for the next 100 years.” states the news release from the NPS.

Over 300 trees were in the path of the construction and have been cut down. After the project is over, the NPS says that “[…] 455 trees (including 274 cherry trees) will be replanted in the area.” The affected trees have already become subject to flooding twice a day and suffer from overwatering. Climate change is seriously affecting this marvelous spectacle of pink flowers, and without implementing changes to reduce humanity’s impact on this Earth, the beautiful blooms may become a thing of the past.

The cherry blossom trees around the Tidal Basin hold a great history of perseverance and friendship. These beautiful trees and their blooms are a reminder of what we need to protect. If we want to keep seeing the cherry blossom trees every spring, we must fight just as hard as Eliza Scidmore in her quest to bring the trees to D.C.