On December the 12th, 2024, Italian journalist and writer Viola Ardone reported the result of a study conducted by the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development, showing terrifying results. The study spanned several countries, both inside and outside of Europe, from Japan to the United Kingdom. The study measured three average traits of people in these countries: their level of literacy, problem-solving skills, and ability to calculate. In all three categories, Italy was among the last. This obviously sparked a huge nationwide debate: How come a whole nation is unlearning reading and writing? Yet, the problem may run far deeper than simply a general lack of literacy. It may be a far deeper, philosophical issue with two faces, that of ignorance and that of nihilism, that spreads over the world through social media and can be solved by an act as old and simple as it is forgotten and thought complex today: reading.

As Ardone reports, one of the main voices within the debate of why Italians are becoming increasingly illiterate is the one arguing that it is the school system’s faults. Schools in Italy generally suffer a lack of funding, and the model encourages great competition among students, which is not always conducive to learning. Yet, in her opinion, the real problem develops after school is over. “The problem is that we really no longer understand what we read, and we no longer know how to draw relations between data to solve a problem.” Slowly, most people who end school as adults “unlearn” what they had studied and value simplicity over complexity (a phenomenon she calls “the talk as you eat” idea, after a popular Italian idiom) in everything they do.

This results in general and ever-growing ignorance. Based on what I have personally seen in my everyday life, I not only agree with her, but I would also add that it’s not just an Italian, or even European, problem. Instead, it is a global problem that affects teenagers, too. I remember a very specific occasion: when I still went to my previous school (before switching to Laurel Springs), I took an Archeology class. At one point, we studied the discovery of Troy, which was previously believed to be only a myth. At one point, the teacher stopped and looked at me with an acquiesced face, as if she were about to do something she had done countless times and was tired of doing. “You see,” she started, “there’s this book, called The Iliad, written by this guy, whose name was Homer, and” and there I cut her short “Professor, with all due respect, I know who Homer was, and I know the Iliad and the Odyssey.” She looked at me amazed. “I mean,” I kept going, “everybody knows the Iliad and the Odyssey.” “Well,” she answered, “let’s hope so.” The obvious implication from this exchange is that the teacher had a vast number of students who had never heard of the Iliad or the Odyssey, which is worrying, to say the least. Thus, the unlearning process is not only engulfing Italy, but also the United States and possibly the whole world. After all, if America is “the city upon a hill” and is experiencing this decline, just think about the rest of the hill!

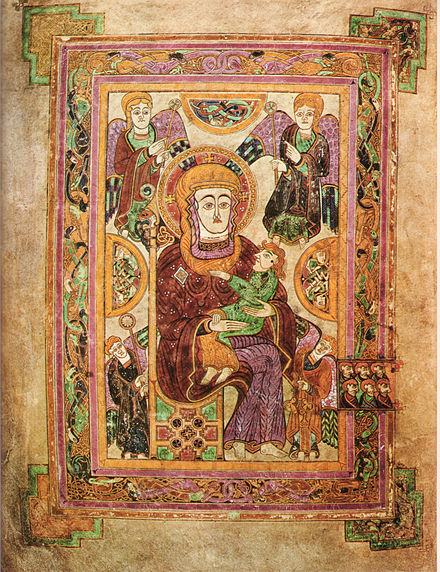

But what is causing it? Why are most people losing basic information about history and literature and anything that came before them? One possible cause that Ardone offers, quoting from Korean philosopher Byung-Chul Han, is that we have lost “the narrative.” Normally, societies (including nations and religions) are held together by narratives, or overreaching stories expressing the values of the society and its view of the world, keeping it together. In the modern world, people are under an endless rain of information through social media, which often offers only fragmented stories. When doomscrolling, you read about the war in Ukraine, then cut to a commercial for new cookies, then go to a YouTube Channel about car races, without ever focusing on any one of these. Submerged by this incoherent mass of stories, people lose sense of larger stories, become unable to follow narratives written in novels, and thus also lose larger, society-defining narratives.

This idea of a narrative holding societies together and that is now being eroded reminded me of a different article, also published in Italy by two philosophers, Andrea Colamedici and Maura Gancitano, about the re-emergence of nihilism in present-day Western society. According to the article, Nihilism was originally defined by Nietzsche as the collapse of shared values that bring people together with a cause. The two thinkers describe modern nihilism as fitting this description but no longer manifesting as a specific current. Rather, it presents itself as a collective refusal of millions of people to engage with the rest of the world by trying to stay in their homes for as long as possible and shielding themselves behind smart working, home delivery, and video streaming. While this trend certainly began with the pandemic, it is becoming increasingly common even long after the virus threat has ended. This results from the widespread conviction that the common people can’t steer history and that the only thing they can ever do is for each to focus on their personal horizons. One of the reasons Colamedici and Gancitano give for this is overload from social media. There is only a set number (150) of meaningful relationships a human being can sustain throughout all of their life, called the “Dumbar number” by anthropologists, and social media cause people to become connected with thousands more than this critical number even in a week. This causes people to try and find repair from the vast world pressing on them within their metaphorical shells.

Taken together, these two ideas suggest that nihilism and ignorance, two of the great issues in the modern age, have the same, paradoxical origin in social media. In these respects, social media is like a global, world-enveloping fog that is both invisible and blinding. Invisible, because they function through cables, satellites, and electromagnetic waves that are not generally visible. Blinding, because they prevent us from noticing what’s immediately before us, our friends and our lives, and instead encourage us to immerse ourselves in a world that becomes increasingly nebulous. But if these two problems have the same origin, then they may have the same solution: the act of reading. As Ardone points out, the main reason why people can no longer read is that they no longer read, mentioning statistics by the Associazione degli Editor (Editors’ Association, in Italian) that show how the sale of books is plummeting. Yet, reading is precisely the antidote for not only ignorance but also nihilism. When we read a book, we are naturally forced to not only follow a narrative word after word, page after page, and chapter after chapter, but also to focus on that narrative completely. Books don’t (usually) skip among seas of random and useless information, and they do not overwhelm us with stories that have inescapable hooks but no real conclusions. They are the complete opposite of social media. As such, they are just what is needed to re-connect oneself to the world, re-learn those shared values that brace against nihilism, and re-gain a basic knowledge of the world.

It’s true, as the old adage holds, that the simpler solutions are often the best.