On March 5, 2025, a very strange series will be released on Netflix. No, it’s not Stranger Things. It is a series bringing together American and Italian actors, taking place in Sicily during the period of Italian unification in the 1860s, and acted out in Italian with English subtitles. Its title is The Leopard. Many Americans who may watch and possibly enjoy the series may not know that it is only the upmost branch of a massive tree that stretches across television, cinematic, and literary history, with an epic historical film as its trunk and ultimately sinking its roots into what may be called “The Great Italian Novel”, beneath a sunbaked Sicilian literary ground.

Indeed, the series was adapted from a 1940s novel written by Italian author Giuseppe Tomasi di Lampedusa, and published in the 1950s. The novel (romanzo in Italian) follows the noble family Salina, in Sicily, as they navigate the massive historical changes happening around them, especially the birth of the Italian nation and the subsequent re-shuffling of society, eventually coming to realize that, as one of the book’s most celebrated quotes holds, “for everything to stay the same, everything must change.” The novel is a powerful portrayal of not only one of the most important periods in European (and ultimately world) history, but also of Sicily’s cultural spirit. For this reason, it is considered among the great masterpieces of Italian literature; it has also been adapted across different media over the centuries. I come from a region in Switzerland where Italian language and culture play a key role, and I recently both read the book and watched the movie. For this reason, I can’t help but race the truly leopard-like leaps of this romanzo over the centuries and across the media.

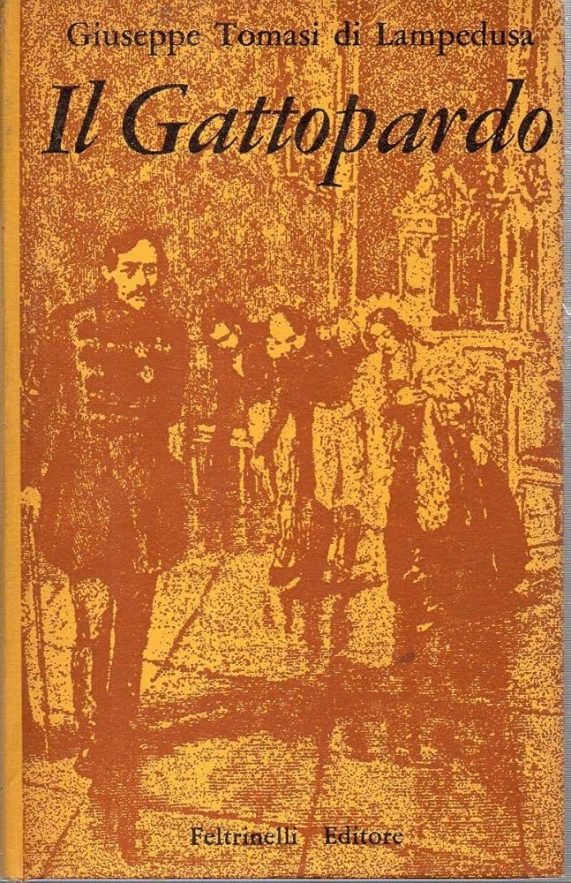

The writing and publication of The Leopard, whose original Italian title is “Il Gattopardo”, was as convoluted as the historical period it takes place. Giuseppe Tomasi descended from an actual noble Sicilian family, and had toyed for a long time with the idea of writing a historical narrative based on his ancestors’ experiences. The catalyst for his writing the romanzo eventually came in the period spanning the two wars, when the end of Russian nobility as a result of the Revolution made him reflect on historical change and how whole ages end and begin. Giuseppe Tomasi then started writing the story by hand while sitting at a coffee shop in Palermo, spending two years immersed in the narrative he was crafting, only stopping in 1957, the year he died. In 1956, he started dictating the first chapters of the novel to Francesco Orlando, a youth whom he was teaching English literature, so that he could type the novel. The various typed copies were then sent out to several of Italy’s most important publishing houses, including Mondadori, as the author continued writing and dictating, but they all turned it down. Eventually, the finished copy was chosen and published by Feltrinelli in 1958, just after Giuseppe Tomasi had died. In a joke of fate, the romanzo was an exploding success, selling 250,000 copies in only eight months, the first Italian novel with more than one hundred thousand copies to be sold. It was also a sensation in academic circles: it won the Premio Strega (the highest literary prize in Italy) a year after it was published. As its planetary success increased, a small controversy erupted over the various versions of the romanzo (the hand-written, the typed, and the published) which, according to Tomasi’s son in the introduction of the book itself, have slight differences in how character names are written and several expressions.

The romanzo takes place during the Risorgimento, or the historical period from the 1840s to the 1860s in which the Italian Peninsula was united into a single nation. Although Italians shared a cultural history and a language, they had been splintered into several kingdoms and city-states, some independent and some, like Milan, under the dominion of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. As Italian historian and writer Alessandro Barbero once remarked, “Europe at that time was a place ruled by absolutist monarchies, yet revolutionaries everywhere were clamoring for precisely the same things that, ironically, bore most people today: political parties, constitutions, and elections”. Most of northern Italy was unified (or rather conquered) by The Kingdom of Sardinia, led by King Vittorio Emmenuele (de jure) and the Count Cavour (de facto), who drove the Austro-Hungarian armies out with help from France. Instead, Sicily and southern Italy were unified by Giuseppe Garibaldi during the well-known Impresa Dei Mille (Expedition of the Thousand), in which a army of around one thousand was pitted against the forces of whole kingdoms. Garibaldi later handed the parts of Italy he had conquered over to the Sardinians, a somewhat reluctant decision, given that Garibaldi wanted Italy to be a democratic republic.

While the characters of real History are Vittorio Emmanuele, Cavour, and Garibaldi, the characters in Giuseppe Tomasi’s story are Fabrizio Corbera, a minor prince of Sicily, specifically the island of Salina, and Tancredi Falconeri, Fabrizio’s nephew who was adopted by the uncle after he lost both parents. The story, in greater detail, follows the Salina noble family and especially their head Prince Fabrizio (also sympathetically known as “Il Principone,” Italian for “big prince”) as they witness the creation of Italy when Garibaldi and his Redshirt armies conquer Sicily, as well as the rise of a new social class, the bourgeoisie, which will replace them as the new ruling class. Prince Fabrizio’s internal monologues, through which he comes to terms with the whirlwinds around him, are given great space. Another key element of the novel are the adventures of Tancredi, who chooses to fight for the Liberals and is torn between two love interests: the Prince’s daughter Concetta, and Angelica, the daughter of a powerful city mayor. These stories and these characters are framed by the vast landscape and culture of Sicily, which is described so vividly that it becomes a character in its own, perhaps the greatest protagonist of the romanzo. The oceanic scope and depths of European history also shines through each word and the descriptions of houses, objects, and monuments.

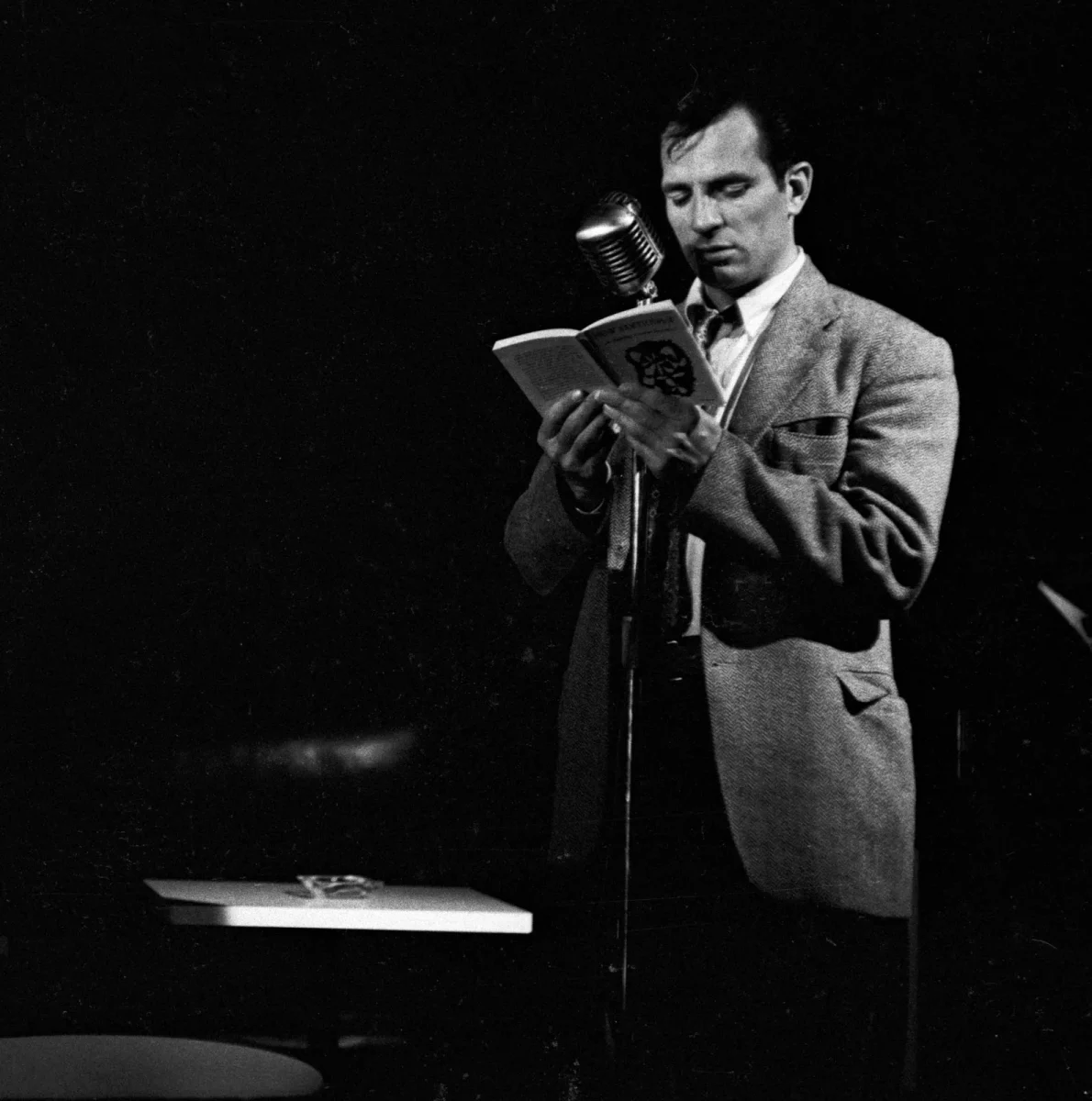

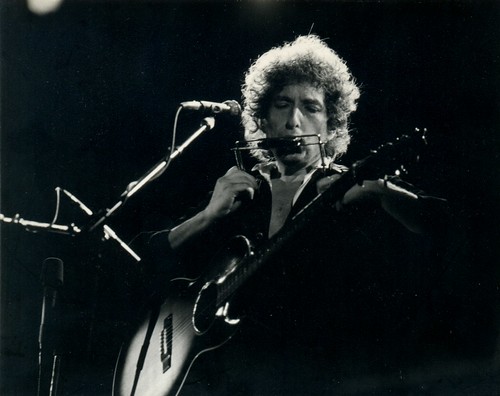

The first adaptation of Il Gattopardo was directed in 1963 by Italian filmmaker Luchino Visconti, starring Golden Globe-winning actor Burt Lancaster as “Principone” Fabrizio and French actor Alain Delon as Tancredi. The film is an epic shot on location in Sicily, known for a climactic scene depicting a ball that lasts roughly one hour. The film won the Palm D’Or at the Cannes Film Festival and is still today considered one of the best films in history. When I personally saw the movie, I noticed it was deeply faithful to the novel. All of the dialogue was taken from the romanzo, which allowed the spellbinding power of Giuseppe Tomasi’s words to pass on the movie.

Now, the romanzo is being adapted once again, this time as a television show produced by Netflix and directed by three filmmakers (Tom Shankland, Giuseppe Capotondi, and Laura Luchetti) and starring Kim Rossi Stuart as Prince Fabrizio, and Saul Nanni as Tancredi. From the teaser trailer recently released, it can be easily seen that this series will greatly diverge from its source material. There may be a subplot in which Tancredi will try to run away with Concetta, which does not happen in the book, where Tancredi is depicted as an upright and dedicated person. Moreover, the Prince will likely be turned into a darker and more villainous character than the original character, as evidenced by a scene in the trailer where he cries for the deaths of revolutionaries. However, these are all speculations, and it remains to be seen what new interpretations directors and screenwriters sourced from both Italy and the United Kingdom will derive from the book.

At one point in Il Gattopardo, Fabrizio Corbera remarks to Father Pirrone, the family’s priest, that the Church was promised immortality, while the nobles’ social class would view even a hundred years as an eternity. It seems that this romanzo has also been promised immortality, as its importance in Europe’s literary pantheon remains and new adaptations are made across the centuries.