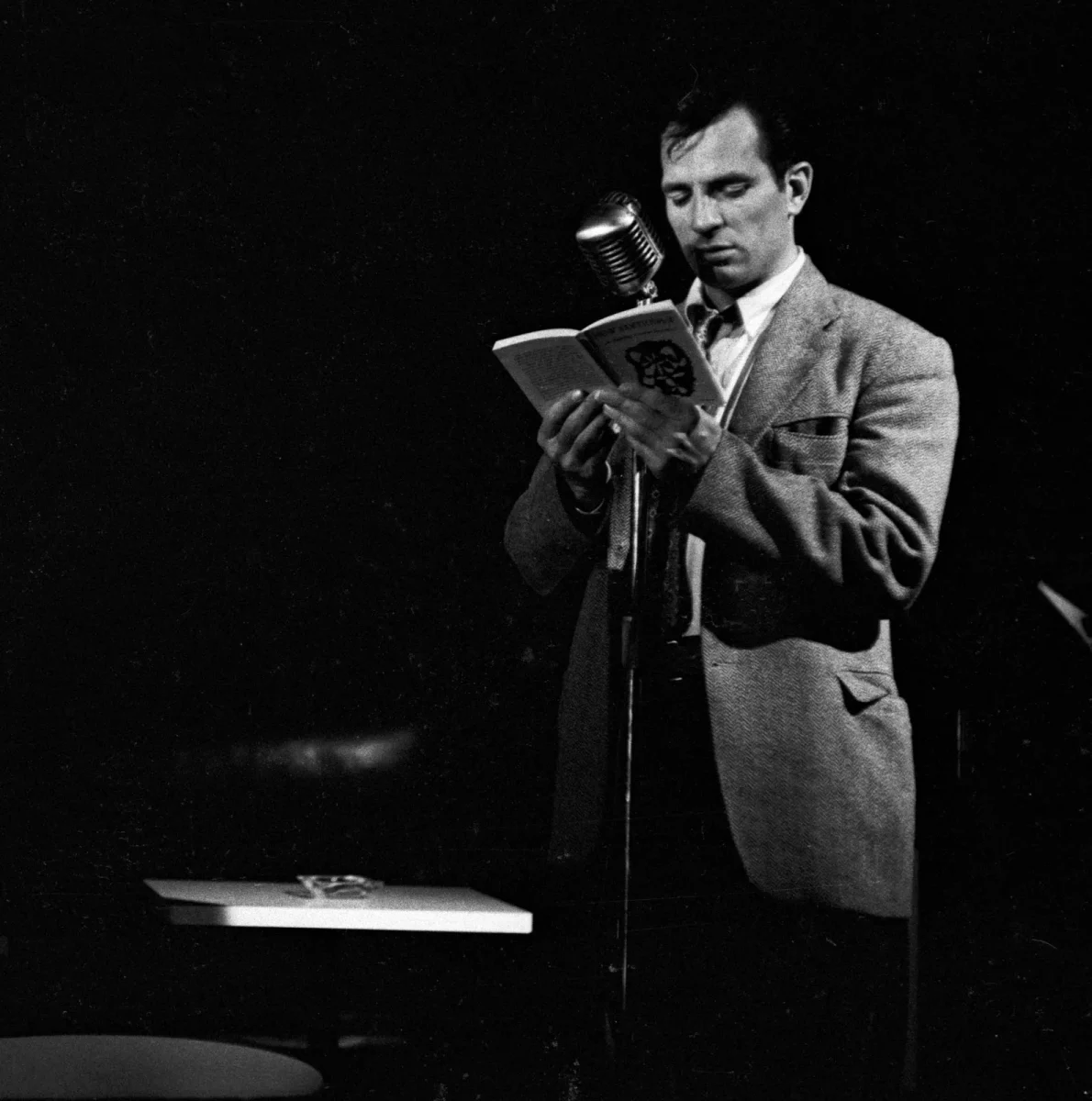

In a post-World War Two societal frenzy of conventionalism, highlighted visually by voluptuous skirts and lettermen jackets, lay a subculture favoring a melancholic color palette, underground bars, and an air of pretentiousness. The word “Beatnik” may evoke several stereotypes such as turtlenecks, berets, or Audrey Hepburn in Funny Face (1957)—that romanticized picture of devoting your life entirely to artistic expression and recording it in a leather-bound journal, hunched over and scribbling sonnets in your local low-lit coffee shop. Whatever your view of Beatniks may be, the term ultimately derives from the Beat Generation: a literary movement and culture that opposed 1950s American mainstream customs.

Pioneered by the likes of Jack Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg, the spirit of non-conformity was the driving force of the Beat Generation, seeping into their literature, art, and music and solidifying the Beatnik identity. One of the defining features of their distinction was a steadfast stance of anti-consumerism.

Following the war, the United States emerged with a determination to restore and enhance the economy as efficiently as possible, lest a 1930s-esque crisis recur. The shift from war to pacifism saw a centralization of mass consumption, with assembly lines accommodating the creation of automobiles and appliances rather than ammunition. While there was a demand for goods, many citizens took caution in spending their war bonds and savings and were already accustomed to the under-consumption regulations that had been in place on the homefront. So, the government and mass media committed to conveying the message that consumption was a civic duty rather than an indulgence, as it was once thought to be. Now, the act of buying was something that improved living standards and created jobs through demand for production. For example, Bride’s magazine told its readers, “the dozens of things you never bought or even thought of before . . . you are helping to build greater security for the industries of this country. . . . What you buy and how you buy it is very vital in your new life—and to our whole American way of living” (Quoted in Cohen 2004, 1).

This urgency to purchase is comparable to the “Run, don’t walk to *Insert corporation name here* to buy *insert object here*!” on your Social Media platforms every day.

However, now, anybody can become an advertiser under the label “influencer.” You don’t have to work at a publication to push products. All you need to market is a mobile device and a suitable amount of charisma when the camera turns on, and you, too, can participate in the growing amount of ads that plague everyone’s screens.

It’s an eerie, almost inhumane experience to be on Social Media as of late. One minute, you’re watching footage of the devastating Palisades Fire waft through palm trees and tear down houses, sprinkling embers across Southern California, and the next, some perfectly airbrushed model is yelling about how you need to buy this new moisturizer because it will change your life. These emotional shifts are akin to the ones seen in the 1950s, from war-time terror to the madness of new products hitting the shelves, only in an unhealthily brief format. The more you scroll, the more meaningless it all seems; you are constantly being sold futile objects under the guise of necessity.

But every once in a while, you’ll strike gold: the de-influencer. De-influencers are the antithesis of influencers, convincing you not to buy objects you don’t need. They post videos or slideshows explaining why you shouldn’t buy the new trendy water bottle because it leaks, or that you don’t need to completely update your wardrobe just because somebody with a blue check mark next to their Instagram handle said skinny jeans were back in style. They also oppose unrealistic life and beauty standards, embracing the messy reality of being human by sharing their own life experiences despite them not being considered picture-perfect.

Paige from Overcoming Overspending is one that has gained significant traction, accumulating millions of views and comments from TikTok users expressing their gratitude. After struggling with impulse spending, she has dedicated her page to teaching financial advice and combatting over-consumption. She regularly posts de-influencing videos, emphasizing putting thought into your purchases, flawed influencer tendencies, and the detriments of consumer culture. Oftentimes, Paige will embody the TikTok influencer, utilizing the “Get Ready With Me” format. This makes for an interesting viewing experience, as the “GRWM” audiences are accustomed to are primarily intended to push products. A contrast between action and idealogy creates an abnormally refreshing tone in comparison to the thousands of short-form videos that reside on the “For You” page.

The Beats originated at a time of prioritization of mass consumption, becoming the first writers to criticize it. Jack Keroauc’s The Dharma Bums, meditates on consumerism in the context of suburbia, describing identical houses and “everybody looking at the same thing and thinking the same thing at the same time.” Allen Ginsberg counters post-industrial industries and flawed systems of labor in his poem Sunflower Sultra, associating it with consumer culture.

Another tendency of consumption in the 21st century is the establishment of aesthetics. Aesthetics, philosophically, is the study of beauty and taste. In Social Media spaces, aesthetics have become subcultures of their own, taking on names like “dark academia” or “cottagecore.” They have evolved into taking part in hobbies, constructing outfits, and even establishing an entire lifestyle centered around the aesthetic of choice. For many, the aesthetic becomes their personality. This is where the line into restriction territory is crossed: where one might develop objections to things simply because they do not align with their aesthetic. This whittles down self-identity to something exclusive and superficial. Instead of your individuality being defined by life experience and the unique tastes one concocts as a response, it is boxed, taped, and labeled by hollow internet terms. Even the Beatniks have become victims of this, being reduced to their aforementioned fashion choices and endearing pastimes. This actively contravenes what their objective was: personal freedom and the acknowledgment of one’s mind and soul rather than frivolity.

If the combat against aesthetics is a battle, de-influencers are on the frontlines. Many shed light on the effects aesthetics have on consumerism, as people feel the need to buy the right clothes, accessories, and decor to fit into the box. They also argue against the idea that selfhood can be defined by a single term.

De-influencing posts are like a breath of fresh air amidst a polluted media space, assuring you that where you are now and what you have presently is enough—that you are enough. You will not find happiness in another package at your door, and you are not at a lack if you refrain from purchasing what everyone else has.

Perhaps de-influencers, with their radical rejection of over-consumption, are the modern members of the Beat Generation. While they may not always be taking a draw of a cigarette and going on shameless harangues about Whitman, Beatnik culture has persisted in unlikely ways. This next group of non-conformists will continue the pursuit of repudiating ideas of singular aesthetics and recognizing the nuanced nature of personhood beyond the material.

Bibliography

Cohen, Lizabeth. “A Consumers’ Republic: The Politics of Mass Consumption in Postwar America.” Journal of Consumer Research, vol. 31, no. 1, 2004, pp. 236–239

Essif, Amien Aaron, “Beat Consumption: The Challenge to Consumerism in Beat Literature” (2012). Chancellor’s Honors Program Projects.