Eyes lined with the long walks of the sixties stare back at you through the cinema screen, and what was once a movie is now something more. “New York Herald Tribune! New York Herald Tribune!” is shouted from the terraced walks of the Champs-Elysee, while Paris washes through the black-and-white canvas trailed by Jean Seberg and Jean-Paul Belmondo.

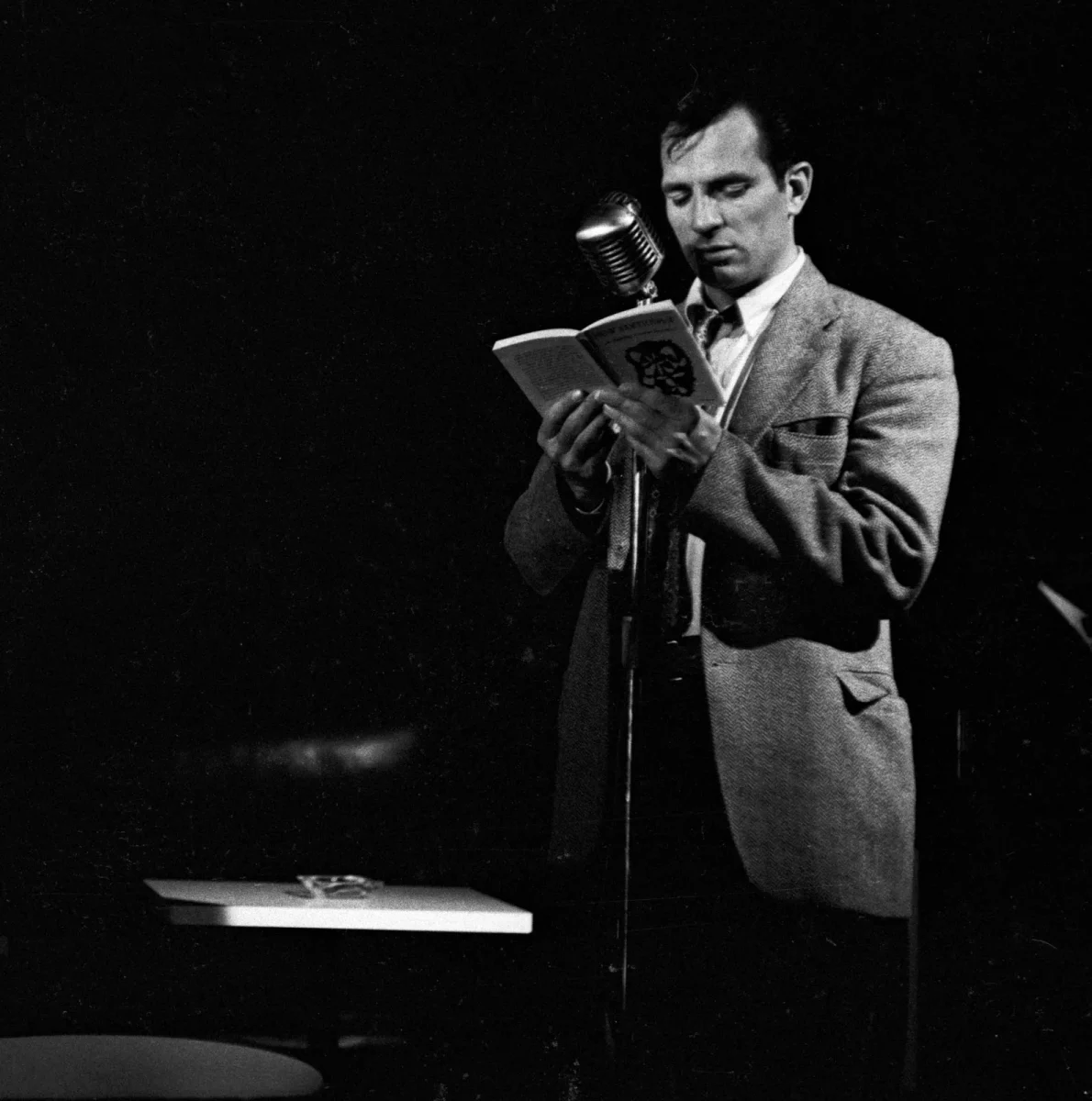

Jean-Luc Godard broke the world of film. Scripts did not exist; actors were given a single Post-It sized paper with three words per scene, like “Michel leaves Paris”. Music scrambles upon dialogue as if edited in a hurry, while the set of reality seeps into the movie without the demand of construction. Godard’s French New Wave was about the spontaneity of art and the fleeting nature of feeling.

“I am really bad with words, I hope you are good at reading eyes”.

Says Madeleine from Godard’s 1966 film Masculin Féminin. During this, the protagonists sit opposite of one another in a café, absorbed into the opposing existences. These poorly lit linoleum or marble floorings, coffee stains on the table, and the swish of customers interrupting the scene have become one of the many material nuances of a Godard Film. It leaves behind whatever “imperfection” of the outside world in place of language, for the conversation shared across these café tables are the persisting thoughts on love and politics that silence the lull of others’ toils. The spark of the café booth has been caught by others after Jean-Luc Godard: from more French films like La Belle Personne or Conte d’été, to the modern Before Sunrise with Ethan Hawke and Julie Delpy.

Godard also speaks behind Madeleine’s hope for one to be “good at reading eyes”, for he uses the eyes as a gateway into the film. The gaze of an actor reaches into the eyes of the audience, and pulls them not into the set of the film but the eyes of the characters: the fourth wall is broken.

Anna Karina fades into the camera, away from the scene of the film Vivre Sa Vie, or To Live Life in loose English. She does not look into the lens as if instructed by a script—as we understand one did not exist—but seems to fall away from her identity as an actress into something hidden. It is not the audience’s purpose to postulate what thoughts she grazes here, yet we do so nonetheless.

Behind the Camera is Jean-Luc Godard, finding his muse, starring actress, and wife Anna Karina on the other side. By breaking the fourth wall of the screen, what stumbles upon the cinephile may be the chemistry between the protagonist and the audience in the breaking, or in Vivre Sa Vie, the connection between the director and his muse.

Stepping back, Jean-Luc Godard’s most famous work, À Bout de Souffle, most explicitly offers commentary on the world of film. Shot in black-in-white while color was indeed prevalent, the 1960 piece follows Michel (Jean-Paul Belmondo) as he accidentally murders a police officer and creates a trail of damage in his various petty decisions. He seeks aid from his somewhat girlfriend, Patricia (Jean Seberg), in seeking refuge before gathering money for Italy.

These traits may construct the Letterboxd blurb, but lack little meaning in the film itself. As the characteristic move in a Godard film, Michel breaks the fourth wall, here in the first scene. The sets are messy and unorganized, featuring Patricia’s plain Paris apartment or the same busy streets of France visited by millions every year, during which music overlaps dialogue that overlaps the noises of the city. This disjointed structure founded the French New Wave movement for Godard, but more importantly, it disrupted the wavelength pattern of standard cinema into a notional piece of art.

In this tangled sprawl is more than a statement on the conventions of cinema; the consistency of the inconsistently unplanned is all but a mistake. Although war, politics, and philosophy are returned upon a café table over coffee, it is the poeticism of reality that is the monologue of the French New Wave. Poeticism is not only love, heartbreak, and war, but the unseriousness and whimsy that is being alive. “One learns to speak well only when one has renounced life for a while”, said Anna Karina in Vivre sa Vie, and the French New Wave is a gaze upon this journey to speaking well: renouncing life.