I was into Irish folktales when the lights went out. One instant, my parents were conversing under the light of the electric chandelier, which bathed the round wooden table in a soft and warm glow, even as the wind rattled against the windows. The next instant, the chandelier went off, along with all other lights across the house. Suddenly, we were in pitch darkness, as if a huge crocodile had swallowed the whole house. A guttural machine sound was heard, giving the impression that the crocodile was burping after the meal. We waited in vain for the generator to start until my father realized it was broken and went in the stormy night to fix it; I roused myself from the world of Sidhe and Leprechauns to help him. We could hardly walk in a straight line: the wind blew and writhed around itself in a vortex, hitting us with branches and dust. As my father worked on the machine and instructed me to fetch the tools he needed, I could not help but gaze at the massive, fiery light on the top of the mountain. That light had appeared as soon as the sun came down and let it become visible, burning through the night like a volcano, but even before that, during the day, we saw the horizon clouded with a wall of smoke, like a wave of ashes ready to sweep over the valley. For me, and for all of California, it was the beginning of an authentic catastrophe, of which this article offers several experiences.

Fixing the generator was nothing less than an odyssey. The wind swept us around, and coldness crept into my bones. When we succeeded, timid lights peered out of our home’s windows like scared eyes, but most of the house still had no current. As I stuttered in my room, searching for toothpaste and brush with my hands, the wind kept blowing and beating against windows, making me think of a giant wolf howling and stomping around the home. I fell asleep in the darkness, lit only by the half-moon, covering myself with as many blankets as I could.

The following morning, the wind had not died down and vast columns of smoke were rising from the mountaintops like grey paint spilling on the blue sky. But, at least we had some power and internet connection. More importantly still, we still had a home.

It was then that I started reading the news about the fires more accurately. It was January the 8th. The day before, a wildfire, later dubbed “Palisades Fire”, had erupted in a neighborhood called Palisades, east of Malibu, inside Los Angeles. While it started out as a brush fire, it quickly spiraled out of control, covering thousands of acres, according to the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection (Cal Fire). The Eaton fire started hours later in a large territory covered by a national forest north of Los Angeles’ downtown area. By the time I read this, neither of the fires had been contained. Lesser ones had also broken out, including the Hurst Fire in the suburban neighborhood of Sylmar, close to San Fernando, and the Auto Fire in Ventura County. More than 20,000 people had been left with no electricity, including the area where the house is, and thousands had to evacuate. Dry weather and powerful winds allowed the fires to quickly spread, but news of unpreparedness also came out, including empty hydrants and shortages of helicopters due to budget cuts.

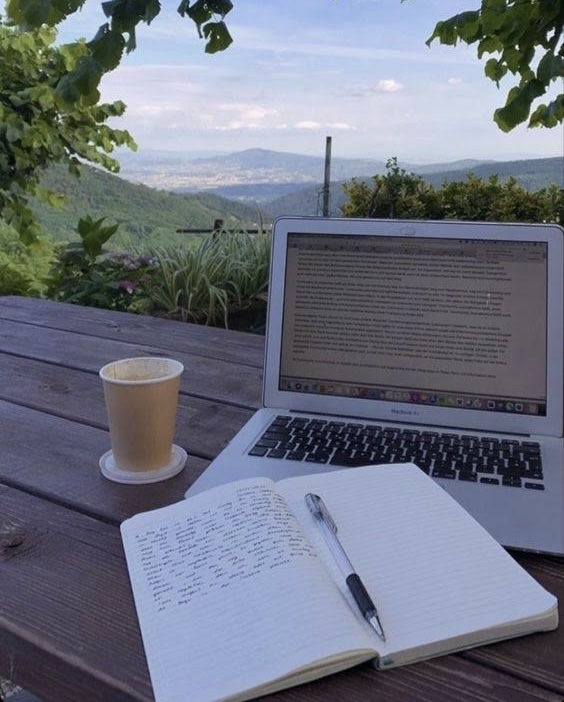

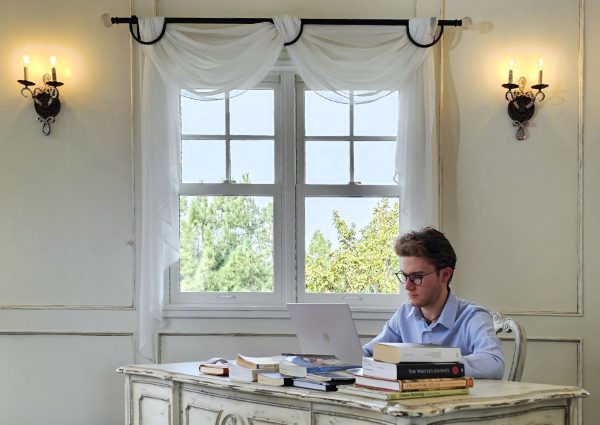

It is one thing to read about evacuations and another to experience (or at least come in contact with) them. When I connected with journalism club that day, I discovered that one of the professors had evacuated, and was joining from a refuge. A friend of my father, B.G, had to also flee from the Eaton Fire with his family. We still didn’t know their position. Two other friends, M.T and L.T., also had to escape the Palisades Fire. The clouds of smoke were occupying the sky like huge birds with foggy wings. Every now and then, solitary helicopters, puny like dragonflies, flew toward the smoke’s source beyond the mountains. And in the midst of all this, I had to take my midterm exams in AP English, AP Calculus, and AP Physics. I had to take them in my parent’s bedroom, as it was the only room with stable wi-fi. We outfitted the room with a table that my mother normally uses to groom the dogs, and it was there that I took the exams.

Indeed, the scariest moment came while I was taking AP Calculus exam on January the 9th. As soon I started it, a warning of a potential evacuation came up about the Kenneth Fire, which had broken out a half an hour before at 3:34 in the San Fernando neighborhood of West Hills. It was the closest fire to our home, and as soon as I had finished the test, my parents started making plans in case we needed to evacuate. My father leased a truck to carry all the dogs and objects, and there was talk of returning to Switzerland, our country of origin. We went to a restaurant to scout for the fire. Still, we did not find anything unusual and were in fact surprised by the attitude of the people around us. All tables were filled with people chatting calmly as if nothing was happening! We drove through the vast expanses of dark houses, with flickering lights here and there challenging the darkness that covered all. Once again, we did not see any fire or smell smoke. We returned a bit relieved, but still went to bed with a heavy heart, ready to evacuate the day after.

Yet, the day after I awoke to a literal light of hope, since one of the very first things I saw was a text from my mother telling me the power was back. I remember switching on and off the lights in the living room out of sheer joy. It is true, as the old adage says, that we can only appreciate light through darkness. We also read in the news that the fires were finally being contained, and my father heard back from B.G: he had found refuge, and the family was safe. They later returned to their home. Unfortunately, M.T and L.T had instead lost their house, but were hosted by a friend of theirs. That day, I took a break from the exams, finishing them the day after with AP Physics.

Throughout the day, the number of helicopters increased. I learned that they were spraying a chemical that easily extinguished the fires and released vast amounts of water vapor. Soon, a whole sea of white smoke was rising from the mountains and washing peacefully over the valley. The burning red lights had disappeared from the horizon at night. Now that I have finished the test, the Kenneth Fire has been put out, and the Palisades and Eaton fires are completely contained and are being extinguished, we are resuming our life as before.

However, while California is not a stranger to wildfires, it is important to learn from this recent catastrophe to avoid something similar from happening in the future. The state government should invest much more money in not only reinforcing firefighters but also in improving the electric infrastructure. In California, as in other parts of the United States, the infrastructure is highly obsolete, as the cables are located on wooden sticks; they easily break, letting deadly sparkles out. Improvements could be carried out with money from taxes, which are high in California. Europe can serve as a model: there, most of the electric infrastructure is located underground or on steel pylons, which do not break. In this way, the risk of wildfires is avoided, and the electric grid is protected by other natural hazards such as snow. If California and other states adopted this European model, then vast losses of life and property would be averted.