Entranced in a dark-academia fog, The Secret History by Donna Tartt isn’t a difficult novel to get lost in. Since I shut its pages and seemingly left its world, it has been inextricably forged in my brain. I don’t doubt that this book has reared its pretentious little head into your internet spaces, most likely on TikTok or respectively “BookTok,” a corner of the app that centralizes literature.

Social media treats this novel like a religious text of sorts, worshiping every word, phrase, and plot point. I am usually not one to follow the advice of “BookTok,” as it doesn’t often align with my personal tastes. But, The Secret History somehow found its way into my hands last fall. It seems Tartt’s words resonate most when the trees are a burnt orange, and the air finds itself being indecisively chilly or fully frigid—as autumn most prominently sees the resurgence of the story, getting more traction online compared to other seasons. This is unquestionably due to its academic themes and overall eerie feeling, akin to that of Halloween or Samhain.

What motivated me to crack open the 544-page thriller?

It could have been Donna Tartt’s intrigue, with her charming Mississippi accent and overly-scholastic outfit choices. Maybe it was the emphasis on aesthetics, characterized by collegiate ivy-covered walls and gothic libraries. Despite these points making up part of its allure, what dragged me in most was the book’s genesis: the first page.

Similar to Homer’s The Iliad, The Secret History reveals its climax in the prologue. The murder of college student Bunny Corcoran at the hands of the narrator and a group of his fellow scholars is explicitly detailed before the book begins. To put it simply, yes, this is what happens in the story. But, like a Greek tragedy, the emphasis is not on what happened, as the audience is fully aware of that before delving in. Instead, the emphasis lies on consequences, and how the characters change in response. The character who experienced the most significant development was undoubtedly Richard Papen, the narrator.

Circling back and honoring the book’s structure, a more detailed description of the plot is required before analyzing themes.

The novel follows Richard and his time at Hampden College in Vermont, where the enchanting aura of a clique of Greek classics students draws him in. They’re intelligent, pretentious, completely under the spell of their eccentric classics professor, yet somehow desirable. Richard wanted nothing more than to adorn himself with tweeds, spend hours discussing Aristotle and Plato, and write casually with Mont Blanc pens just as they did. Little did he know, that roping himself in with them would rope him into Dionystic rituals and the murder of Bunny Corcoran, a member of the group who they decided no longer fit into their mold of intellectualism.

Truthfully, the plot is much more nuanced than this, and I could spend hours dissecting each point, but for the sake of brevity, simplicity wins today. Several major themes portray this novel. One of them is the danger of romanticism. A theme that should resonate significantly in the age of social media and aesthetics, the dangers of romanticism can be seen in each character of this book. Richard, specifically, describes his “fatal flaw” as being a “morbid longing for the picturesque at all costs.” This longing for beauty is what blinds him to seeing the Greek class’ ignorance and lack of redeeming qualities. Each member of the clique is practically drunk on the idea of perfection and patricianism, detaching themselves from reality, and emphasizing Donna Tartt’s purpose of criticizing elitism in academia.

Another theme worth mentioning is the fact that every action has a consequence. Unlike a Greek tragedy, there is no divine guidance in this book (despite what the characters might think.) There is no god or goddess gliding down from Olympus to assist in the trials and tribulations that occur, and every character is met with the harsh reality that comes with their actions, hence the lack of a happy ending. A rude awakening, sure, but considering their crimes and little to no amount of remorse, I don’t exactly feel bad.

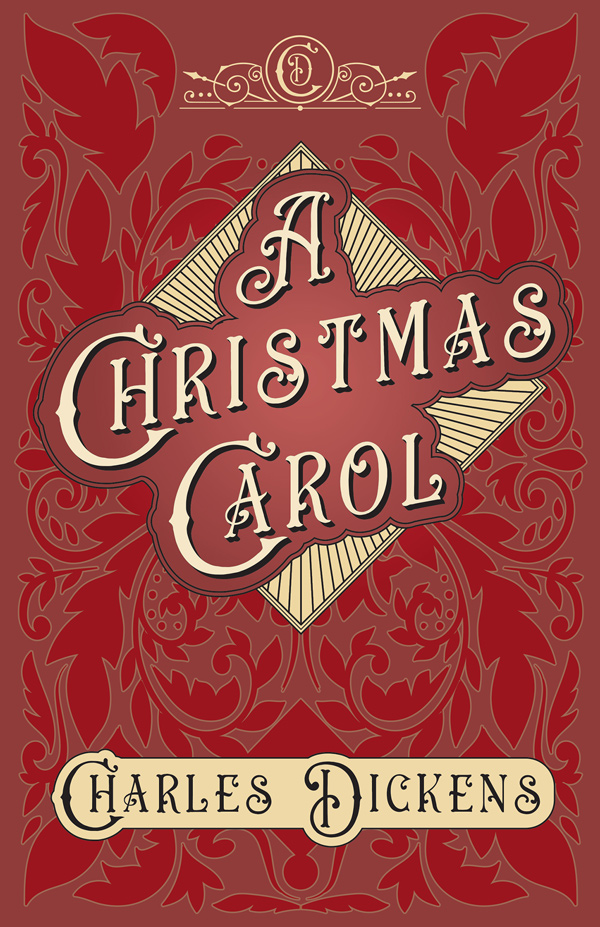

Donna Tartt’s writing style is on a Dickensian level, making every detail of the book glimmer despite how dark it may be. Even just describing the weather in the mountains, or how the sun hits the trees outside of Richard’s dorm, she paints an intricate picture. It’s hard not to feel bereft after putting the book down and retiring from the mural she had so beautifully put together. Her educated references to classic literature and film make her work that much more admirable.

This detailed style of writing, while also stemming from talent and practice, can be attributed to the sense of familiarity she had with colleges like Hampden College, and with people similar to the Greek class. The novel is based on Tartt’s time at Bennington College, and the characters are loosely based on her fellow classics majors.

I finished this book, 544 pages and all, in one week. A year later, I am still thinking about it, dissecting it, analyzing it, and writing about it. If you enjoy psychologically thrilling novels with relevant themes and flawless prose, you’ll certainly enjoy The Secret History as much as I did. I will leave you with a quote that lies in the epigrams of its pages, which I, and presumably Donna, believe sets you up perfectly to read the novel:

“I enquire now as to the genesis of a philosophist and assert the following: I. A young man cannot possibly know what the Greeks and Romans are. II. He does not know whether he is suited for finding out about them” – Friedrich Nietzche